Jim Riordan and Stuart Thompston

Introduction

Communist sports policy in Europe is dead. It lives on in China, Cuba and North Korea. It was not everywhere identical; it did not feature highly in terms of national priorities in the less economically advanced communist nations such as Albania, Vietnam and Cambodia, but in the Soviet Union and in most of the East European communist States it assumed major importance.

The rapid collapse of Soviet-style communism throughout Eastern Europe and of the nine nations there that subscribed to it (with variations in Albania and Yugoslavia on the totalitarian or ‘state socialism’ model) provides an opportunity to examine ‘communist sports policies’ and the impact they had on sport and popular perceptions. It also provides an opportunity to examine their parlous state in the post-communist era; the impact of the Americanisation of sport on the former communist world; the extent to which the communist model influences current policy there; and the apparent desire of Russia’s post-Yeltsin leadership to bring about a revival of sport and physical education.[1]

The Communist Model

The key reason for the worldwide interest in communist sport was that its success, particularly in the Olympic Games, attracted considerable attention. A less remarkable, though perhaps more far-reaching aspect of communist sport, however, was the evolution of a model of sport or ‘physical culture’ for a modernising community, employing sport for utilitarian purposes to promote health and hygiene, defence, labour productivity, the integration of a multi-ethnic population into a unified state, international recognition and prestige; and what we might call ‘nation-building’. After all with the exception of East Germany, and to some extent Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland, communist development was initially based on a mass illiterate, rural population. It was this model that had some attraction for nations in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

In most communist States, therefore, sport had the quite revolutionary role of being an agent of social change, with the State as pilot. After revolution or liberation there was rarely a leisured class around to promote sport for its own disport, as there was, say, in Victorian England. There was, in any case, Soviet distaste for the kind of social privilege reflected in ‘bourgeois amateur status’.[2]

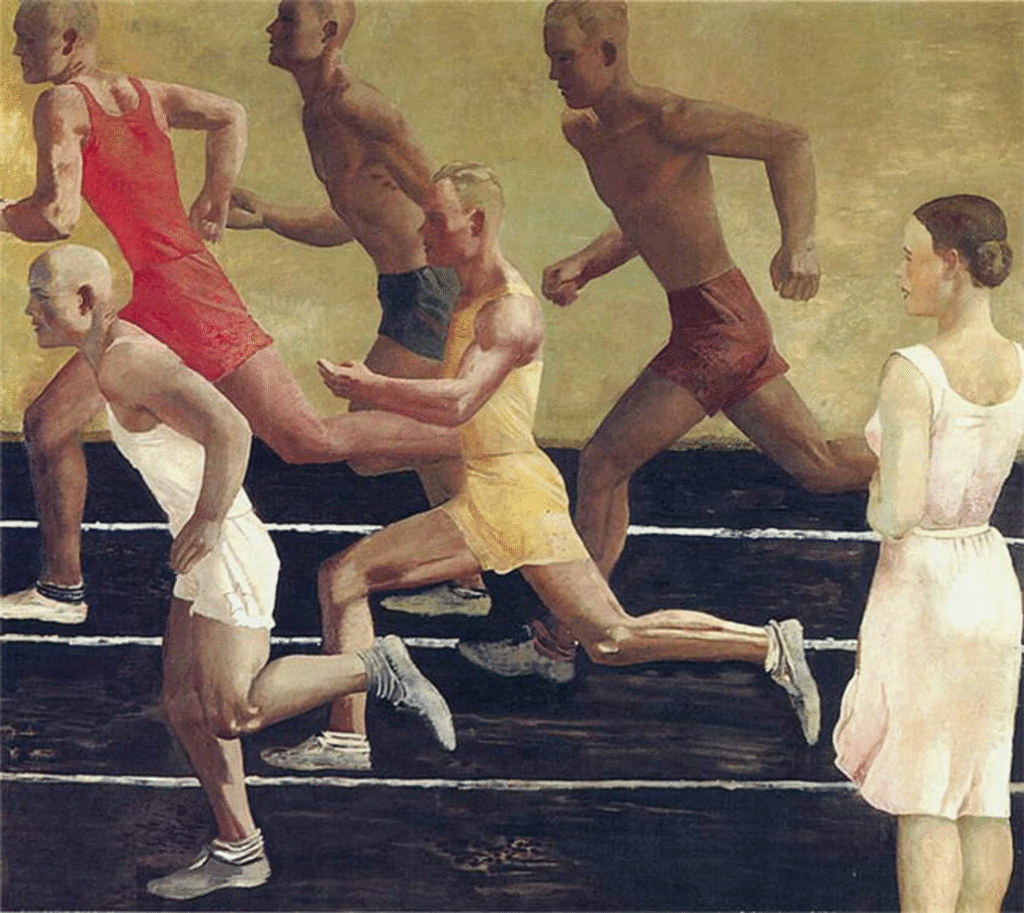

Further, partly under the influence of Marxist philosophy that stressed the inter-dependence of the mental and physical states of human beings, many communist countries emphasised the notion that physical culture is as vital as mental culture to human development, and that it should be treated as such both for the all-round development of the individual and, ultimately, for the health of society. Sport also had the added advantage of providing diversions in an economic system, where, in the early stages of development at least, the priority given to heavy industry meant that consumer goods were often in short supply.

The Priorities of Communist Sports Policy

The following would seem to have been the main State priorities assigned to sport in communist development:[3]

Nation-building. All communist States faced problems of political stabilisation and of economic and social development; some were confronted with the serious problem of integrating ethnically diverse populations into a unified State. A key issue here is that of nation-building – the inculcation of political loyalties into the population as a whole, transcending the location.[4] Not only was this a key problem facing post-revolutionary Russia, China and Cuba, it has been equally relevant to post-liberation modernising societies in Africa and Asia.

What better than sport to help the regimes in such societies promote the building of strong nation States? After all, sport, with its broad relevance to education, health, culture and politics, and its capacity to mobilise people (pre-dispose them towards change), may uniquely serve the purpose of nation-building and help foster national integration. It extends to and unites wider sections of the population than probably any other social activity. It is easily understood and enjoyed, cutting across social, economic, ethnic, educational, religious and language barriers. It permits some emotional release (reasonably) safely, it can be relatively cheap, and it is easily adapted to support health and social welfare objectives.

And it is here that the sports introduced by Westerners at the turn of the century in China, Russia, Cuba and other developing States have some advantages over indigenous folk games in that the latter are often linked to festivals which mainly take place annually; they have served only as a means of expressing tribal or ethnic identity whereas modern sports have served as a means of expressing national identity. It has, therefore, been modern sports that communist States took up and promoted.

Integration. Bound up with nation building has been the State-desired aim of integrating a multinational population, often in transition from a rural to an urban way of life, into the new nation State. Many communist societies were loose federations of diverse ethnic groups: different colours, languages, traditions, religions, stages of economic growth, and social prejudices. By way of illustration let us take the world’s two largest communist countries. The billion plus people of China consist of at least a dozen major ethnic groups, so that the country is divided into 21 provinces and five ethnic autonomous regions. For its part the USSR was a multinational federation of over 290 million people containing 100 or more distinct nationalities.[5] The country was administratively divided into 15 Union Republics, each based on a separate ethnic group.

The governments of both these great countries quite deliberately took Western sports from town to country and, in the case of the USSR, from the European metropolis to the Asiatic interior, and used them to help integrate the diverse peoples into the new country and to promote a patriotism that transcended petty nations and ethnic affiliation.

Defence. Since many communist States were born in war and lived under constant threat of war, terrorism and subversion, it is hardly surprising that defence has been a prime consideration for most communist governments. Sport was, therefore, often subordinated to the role of military training. In some countries the system was best described as the ‘militarisation of sport’. The role of the military in sport was further heightened by the centralised control of sports development.

It should be remembered that both China and the USSR had numerous borders with foreign States – 14 in the case of China and 12 in that of the former Soviet Union. Moreover, even in recent times both countries lost immense numbers of people in wars. For example, in World War II China lost 13 million and the USSR 27 million, by far and away the greatest human losses in the history of war.[6]

In both countries, as well as in certain other communist States (e.g., North Korea and Cuba), the sports movement was initially the responsibility of the armed forces and even recently was dominated by the instrumental needs of defence and by military or paramilitary organisations. In the Soviet Union, in the post WWII period, the vast All-Union Voluntary Society for Collaboration with the Army, Air Force and Navy, DOSAAF, exceeded 100 million members, supported by 100,000 instructors who were mainly reserve officers. Open to children aged 14 and over it was by far the largest military-sporting organisation in the world. Its 315,000 branches provided excellent facilities for sports that had a military value such as shooting, orienteering and swimming.[7] In fact all communist States had a country-wide fitness programme with a bias towards military training, modelled on the Soviet ‘Prepared for Work and Defence’ (GTO) system, which was originally modelled on the standards set by Lord Baden Powell for the Boy Scout ‘marksman’ and ‘athlete’ badges, and significantly was called ‘Be Prepared for Work and Defence’.[8] In East Germany it was echoed in the official slogan of the German Gymnastics and Sports Association (DTSB), ‘Ready for Work and for the Defence of the Homeland’.[9]

All communist and some non-aligned States had a strong military presence in the sports movement through armed and security force clubs (e.g., Honved, Dinamo, Vorwärts), which also provided military sinecures for more or less full-time athletes.

Health and Hygiene. Of all the various functions of State-run sport in communist States, that to promote and maintain health always took precedence. Regular participation in physical exercise was to be one means – relatively inexpensive and effective – of improving health standards rapidly and a channel by which to educate people in hygiene, nutrition and exercise.[10] For this purpose a new approach to health and recreation was sought. The name given to the new system was physical culture. Physical culture stood for ‘clean living’, progress, good health and rationality, and was regarded by the authorities as one of the most suitable and effective instruments for implementing their social policies, as well as for the social control implicit in the programme.

As industrialisation got underway in the USSR at the end of the 1920s, physical exercise also became an adjunct, like everything else, to the Five-Year Plan. At all workplaces throughout the country a regime of therapeutic gymnastics was introduced with the intention of boosting productivity, cutting down on absenteeism resulting from sickness and injury, reducing fatigue, and spreading hygienic habits among millions of new workers who had only recently inhabited bug-infested wooden huts in the villages. This Soviet-pioneered health-oriented system of sport was either imposed upon or adopted by every State that subsequently took the road to communism.

Social Policies. There are many facets of social policy relevant to sport that concerned communist States. These included combating crime, particularly juvenile delinquency, fighting alcoholism and prostitution, attracting young people away from religion and especially from all-embracing faiths like Islam. One aspect of the use of sport for social policy was the belief that it could make some contribution to the social emancipation of women.

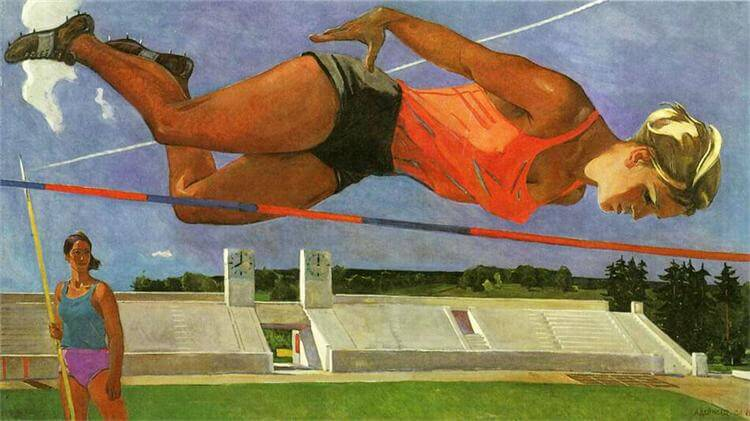

The impact on women’s sport has been considerable, even though the overall emancipation process has been somewhat protracted and painful in communities in which women have, by law or convention, been excluded from public life and discouraged from baring face, arms and legs in public. Some multi-ethnic communist countries quite deliberately used sport to break down prejudice and gain a measure of emancipation for women. This was a conscious policy in communist States with a sizeable Muslim population including Albania, the USSR and Afghanistan.

International Recognition and Prestige. For all young countries trying to establish themselves in the world as nations to be respected, or even recognised, sport may, uniquely, offer them an opportunity to take the limelight in the full glare of world publicity. This has been particularly important for those nations confronted by bullying, boycotts and subversion from the big powers in economic, military and other areas. This has applied as much to the Baltic States with regard to Soviet Russia as it has to Cuba and Nicaragua with regard to the United States.

This has put particular responsibility on athletes from communist nations in that they have been seen by political leaders as encouraging a sense of pride in their team, nationality, country and even political system. Not all communist athletes accepted that role, as witnessed by the post-communist outbursts in Eastern Europe during 1989.

Where other channels have been closed, it does seem that success in sport helped such countries as the USSR, China, Cuba and East Germany as well as many other States in the developing world to attain a measure of recognition and prestige, both at home and abroad. As Pravda put it in 1958:

“An important factor in our foreign policy is the international relations of our sportsmen. A successful trip by the sportsmen of the USSR of the people’s democratic countries is an excellent vehicle of propaganda in capitalist countries. The success of our sportsmen abroad helps in the work of our foreign diplomatic missions and of our trade delegations.”[11]

In the case of East Germany, however, the desire for prestige through sporting achievement did lead to excess. The post-communist exposure of institutionalised doping has made the previous ‘Sportwunder’, East Germany, much more understandable.[12] Nevertheless, competitive sport is unique in that for all communist countries, including the USSR and China, it was the only medium (apart from the early years of space conquest) in which they have been able to take on and beat the economically advanced nations. This took on an added importance in view of what their leaders traditionally saw as the battle of the two ideologies for influence in the world. These feelings were reciprocated in the West. In the cold war era of the 1950s the victories of the US Olympic team became symbols for Americans of the triumph of democracy over communism. Sport added an important dimension to the Cold War.[13] “The class struggle also manifests itself in the sphere of physical culture and sport” proclaimed one East German source.[14] Old enmities in sport linger on. There were echoes of past ideological battles at the 2002 Winter Olympics, when alleged bias against Russian competitors moved one Russian commentator to observe that it was quite like former Soviet times when “the Olympics were more than sports; they were war”.[15]

The Post-Communist Era

The rapidity of post-totalitarian change in all areas, sport included, in Eastern and Central Europe and the one time Soviet Union would seem to indicate that the élite sports system and its attainments, far from inspiring universal national pride and patriotism, tended in some quarters to provoke apathy and resentment. This appeared to be more evident in those States – Hungary, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and the German Democratic Republic – that had ‘revolution’ and an alien sports system and values thrust upon them, contrary to their indigenous traditions. A similar mood has been apparent, too, in Islamic areas of the old USSR.

Sports stars were seen as belonging to a private, élite fiefdom within the overall domain; they were not part of a shared national achievement, let alone heritage. That is not to say that in societies of hardship and totalitarian constraint, and in the face of Western arrogance and attitudes that were sometimes tantamount to racial prejudice, the ordinary citizen obtained no vicarious pleasure in her/his champion’s or team’s performance. But overall, the dominant attitude was one not entirely different from Western class attitudes to sports and heroes that are not ‘ours’ (e.g., the ambivalent attitude of many Westerners to Olympic show-jumpers, yachtsmen and fencers).

On the other hand, in countries like the now defunct Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, as well as the Slav regions of the former Soviet Union (the Ukraine, Belarus and Russia), the patriotic pride in sporting success would appear to have been genuine. One reason for this may be that the socialist revolution of 1917 in the old Russian Empire, and of 1946 and 1948 in the cases of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, came out of their own experience and had some measure of popular support. The same might be said of China, Cuba and Vietnam.

This is not to say that it was communist ideology that motivated athletes or that Marxism-Leninism was responsible for sporting success, particularly at the Olympic Games. A more compelling reason was that the sports system grew up and was integral to the building of a strong nation-state, which generated its own motivational forces and patriotism. The same central control and planned application of resources, allied to State priorities and direction of labour, which initially achieved such remarkable success (in relatively backward States like Russia, China, Bulgaria and Romania) in constructing the infra-structure of socialist society, provided conditions that were more conducive to discovering, organising and developing talent in specific sports than those of the more disparate and private Western systems. It should be added that with the participation of the Soviet Union in the 1952 Helsinki Games, after an absence of 40 years, communist sport was oriented towards Olympic success.[16] Complaints from the West, and particularly the United States, that Soviet and East European athletes were not truly amateurs because of government support were somewhat hollow, given that most American athletes were actually supported by American Universities solely for their athletic prowess.[17] However, it is the case that the far from privileged Soviet athletes fared less well in the fully professional and commercial sports of the West: football, basketball, boxing, rugby, motor racing, tennis and baseball.

In the post-communist era the inheritors of the sports system that evolved during the communist years have been faced with a choice of how sharply they should break with the past and adopt a pattern of sport based on market relations. ‘Westernisers’ in Eastern Europe, with public support nourished on a reaction to the communist past, aided by those Westerners eager to see old communist States join the ‘free’ world, and abandon socialism, central planning and social provision, seem bent on rejecting the past in toto and embracing its antithesis.

With the post-modern emphasis on instant gratification, the traditional individual sports of gymnastics, swimming and some events in athletics are losing much of their popularity. This is a universal trend. US sports like baseball, American football and in-line skating are making inroads into traditional European, including East European, sport.[18] Women’s gymnastics is in large measure converting to aerobics but at least this is preferable to the plight of some aspiring women gymnasts (and ballet dancers) from the former Soviet Union who now ply their skills in Western strip bars.

These trends are discernible all over Europe. Now that the communist challenge has withered on the vine – with the significant exceptions of China and Cuba –the symbolic rivalry between communism and capitalism (USSR v USA, East v West Germany, Cuba v Latin America) has melted away. What has taken its place?

With the fall of communism, three major global trends are discernible: ‘commodification’, ‘gladiatorisation’ and internationalisation’. Commodification can be characterised as the development of sport into a much more commercialised product. It is used as a marketing instrument to promote commercial products or tourist activities. As a consequence, some traditional sports and clubs are becoming ‘outmarketed’ by commercially oriented, privatised sports organisations. It is likely that in future some sports will greatly decline both as participant and spectator pursuits. Other sports, like boxing and wrestling, could turn into ‘fairground attractions’ on the Western model, being displayed in casinos and on TV screens. What is meant by ‘gladiatorisation’ is the trend towards increasingly gladiatorial and violent (or simulatedly violent) spectator sports that lend themselves well to television – boxing and wrestling, car and motorbike racing, as well as US sports like American football, baseball and in-line skating. This can be seen as a consequence of the growing domination in society of television in general and of the richest, tentacle-like TV companies of the USA in particular. The domination of TV advertising is further encouraging the internationalisation of sport. The contests favoured are those that have resonances in many countries and those that attract most advertising revenue, such as the Olympic Games and the various world cups. As a consequence, localised competitions continue to diminish.[19]

How have these global trends impinged on ex-communist States? In some (Russia, Belarus and Bulgaria), sport has become a hybrid of the worst of both worlds, retaining the bureaucracy of the old and adding only the exploitation and corruption of some forms of western sport. Other countries, however, have used sport in the new era to further their recognition as independent States in the world (Croatia, Slovenia, Lithuania, Estonia and Slovakia).[20] They prefer their own independent teams to the former system of combined effort and success.[21]

Such a radical shift of policy is bound to cause a tinge of sadness in those who have admired aspects of communist sport down the years – not only because it provided good competition with the West. Elitist as the old system may have been, it merits saying that it was generally open to the talents in all sports, probably more so than in the West. It provided opportunities for women to play and succeed, if not on equal terms with men then at least on a higher plane than with Western women. It gave an opportunity to the many ethnic minorities and relatively small States in Eastern and Central Europe and the USSR to do well internationally and to help promote that pride and dignity that sports success in the glare of world publicity can bring. Nowhere else in the world has there been, since the early 1950s, such reverence by governments for Olympism, for its founding father, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, for Olympic ritual and decorum.[22] One practical embodiment of this was the contribution to Olympic solidarity of the developing nations through the training of Third World athletes, coaches, sports officials, medical officers and scholars at various Soviet colleges and training camps. Much of this aid was free; none of it was disinterested. It went to those States whose governments generally looked to socialism rather than capitalism for their future. Further, no-one outside the Third World did more than the communist nations to oppose Apartheid in sport and have racist South Africa banned from world sports’ forums and arenas.[23]

During the 1990s the international challenge of former communist States was diluted through lack of State support and ethnic divisions. Compounding the philosophical differences over the role of State sponsorship in sport, the economic difficulties of the Yeltsin era precluded financial support at anywhere near the previous level. For ten years the Russian government virtually ignored sport.

Such neglect had international repercussions too. In Russia and indeed right across the Central and Eastern European plain the support to students from the developing world came to an end. Such students of medicine and engineering as well as of sport have had to go home as their support grants have run out. Instead of their former status as promoters of international sport, ex-communist States have become competitors with other poor nations for development aid from the West.

However, it is at the grass roots level that the decline in physical recreation and sport has been most corrosive. Many families in Yeltsin’s Russia spent far more on alcohol and tobacco than they did on sport. The free trade union sports societies, as well as the ubiquitous Dinamo and armed forces clubs have, in may cases, either closed or given way to private sports, health and recreation clubs. Women’s wrestling and boxing now attract more profit than women’s chess and volleyball. Some 40% of the sports schools and sports clubs that previously existed in the country were closed down and some 20% of athletic facilities were lost too. At a State Council meeting in January 2002 to discuss the future of physical fitness and sport the president, Vladimir Putin, cited the case of Russia’s speed skating championships, which had to be held in Germany because the country did not have any winter sports centres that met current world standards.[24]

Some of the country’s leading sportsmen and trainers during Yeltsin’s decade of sporting neglect chose to capitalise on their skills by seeking posts abroad. A case in point was the celebrated ice hockey player, Vyacheslav Fetisov, a product of one of the Soviet era children’s sporting schools.[25] During the 1999-2000 season he was assistant coach of the New Jersey Red Devils. He later coached the Russian ice hockey team at the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics. Unusually amongst such ‘foreign legionaires’, as they are dubbed in Russia, Fetisov has been drafted in to help the revival of Russian sport. While very little use has been made of other sports personalities working abroad Fetisov has been appointed chairman of the new State Sports Committee. Its former chairman, Pavel Rozhkov, has been made Fetisov’s deputy. What is also significant is that this committee has had its name changed from the Russian Federation State Committee on Physical Fitness, Sports and Tourism. It would appear to signal a more focused approach towards promoting sport.[26]

Arguably the personal interest of the President has played a major part in this renewed concern to promote sport, but also significant is the residual pride in the sporting achievements of the Soviet era and the apparent desire to return to the forefront of world sport. The Russian press were clearly angered by the disqualification at the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics of the Russian women’s ski relay team after one of its members was found to have high levels of haemoglobin in her blood. The press were also upset by the ‘controversial’ decision to award the gold medal in the ladies figure skating competition to the American Sarah Hughes rather than the Russian, Irina Slutskaya. Most of all it was incensed by the attempts made to strip the Russian figure skaters of their gold medal after Canadian protests at the alleged partiality of the French judge. In the event both the Russian and the Canadian figure skating pairs were awarded gold medals.[27]

Russian discontent at these alleged injustices went wider to encompass an attack on what they viewed as a discrediting of the Olympic ideal. In place of the old rivalry of ‘socialism’ and ‘imperialism’ with the reciprocal boycotts of 1980 and 1984 has come something far worse than politics, namely money. As the correspondent of Rossiyskaya gazeta put it:

“Business has set its eyes on the Olympic movement. I’m not going to talk about the various profits the Olympic Games can generate – beginning with the decision on where to hold them and ending with athletic achievement (for example, an athlete ‘must’ win first place in order to get product endorsements).”[28]

The correspondent even went so far as to equate what he saw as the discrediting of Olympic principles at the Salt Lake City Games as being as momentous a turning point as the events of 11th September 2001.

From a British and West European perspective the Salt Lake City Games belatedly dragged Russia into the real world of international sport. Its previous success in international sport arguably blinded it to the Americanisation of sport: the ‘winning isn’t everything – it’s the only thing’ attitude.[29] As a British sports commentator recently observed, Olympic sport changed after the 1984 Los Angeles Games. Thereafter the Games:

“became big business and cities fought and flocked – and bribed – for the lucrative honour of holding them … Sport has changed beyond measure. The way we watch sport and understand it has also changed. And the principal reason for the change is America: the way Americans play their sports and the extent to which they value their sports.”[30]

The outcry in Western Europe after the 1999 Ryder Cup golf competition, when the Americans ‘chucked all sporting conventions of decent behaviour out of the window in an incontinent, gloating and premature celebration’, exemplified the changes in international sport, which Russia found so galling at the Salt Lake City Games.[31]

President Putin evidently regretted the passing of the old idea of sport. He felt moved to comment on the handling of the Salt Lake City Games, attacking the new president of the International Olympic Committee, Jacques Rogge, for his ‘pro-American policy’. But Putin seems to have recognised that for good or ill the new international sporting culture is here to stay and Russia will have to adapt to it. He hinted as well that Russia’s sports functionaries were in for a difficult ‘performance review’.[32]

Russia’s early exit from the Summer 2002 football World Cup evoked similar dissatisfaction. The Russian media poured scorn on the Russian coach, Oleg Romantsev, accusing him of ‘cowardly defensive tactics’ against Belgium, a game Russia only needed to draw to progress to the next round.[33] At the street level Russia’s defeat against Japan sparked off a riot amongst some of the 8,000 spectators who were watching the match on a giant TV screen in Moscow’s Manezh Square.[34] Russia’s desire to be a leader, if not the leader, of world sports evidently remains undimmed.

Does this, however, indicate that the Russian media and political élite are primarily motivated by issues of civil disturbance and national prestige? Certainly the football riot referred to above provided the press with an opportunity to belabour the former Yeltsin government for de-sensitising young people to violence by feeding them an unremitting diet of American films with their focus on murder and brutality. The resultant neglect of organised leisure time activities and sport ends up, it is claimed, with teenagers not knowing how to direct their energies.[35] Although national prestige from sporting success may well be uppermost in the minds of the general public, there is evidence to suggest that, as in the communist era, the primary motive of the government in its recent drive to boost physical fitness and sport is concern about the physical well-being of the population. The head of the State Council Praesidium task force set up to enhance the role of physical fitness and sport, the Chelyabinsk Province Governor, Pyotr Sumin, made clear in January 2002 the government’s concern at the nation’s health. He indicated that 50% of children in Russia were in poor health, while over the past ten years mortality had increased by 37%. Additionally the number of teenage drug addicts had increased 17-fold over the same period.[36] Putin voiced similar concerns, pointing out that over the past two years overall morbidity had risen by 24.4% among children, 32% among teenagers, and 13.3% among adults.[37]

Putin’s New Physical Fitness Programme

Ending a decade of neglect of physical fitness and sport became, in 2002, an ‘issue of considerable urgency and great importance to the country’. At its 29th January meeting the Praesidium of the Russian Federation State Council discussed a government plan involving the construction of 1,000 physical fitness and health complexes, as well as increasing the number of neighbourhood sports and recreation centres from 4,300 to 14,000. In schools six to eight hours a week would be devoted to physical education instead of two. It was also mooted that sport might be popularised by Putin’s proposal to establish a nationwide TV sports channel. As well as the physical well-being of the population as a whole Putin also showed interest in the well-being of élite athletes and coaches. In addition to improving their pension security he directed the government to introduce monthly stipends of at least 15,000 roubles for the country’s top 1,000 athletes. Were the programme to be implemented in full, it was estimated[38] that over the four to five years of its life the cost would be some 40 to 50 billion roubles and while hopes were expressed that some of this might be met by private sponsorship, the bulk of the funds were clearly going to have to come from the government. It is also significant that the proposed nationwide campaign to persuade as many people as possible to become actively involved in physical fitness and sport has echoes of the communist era programme, ‘Prepared for Labour and Defence’. Admittedly the proposed new slogan, ‘For a Young and Healthy Russia, Let’s get started with the President’, may not have the resonance of its predecessor but it does suggest where the government’s present priorities lie.[39] Only time will tell whether these good intentions will become reality.

Conclusion

The further we get from the break up years of 1989-1991, the more clearly a new sports nationalism is seen to be emerging. International rivalries are resuming, no longer rooted in political ideologies, but in ‘good old’ nationalism. The new Russia promises to be the embodiment of this, although it is dependent on the revival of her economy, which would allow Putin’s ambitious programme for physical recreation and sport to be implemented in full. On a global basis the Americanisation of sport has combined that ‘good old’ nationalism with strident commercialism. The obverse side of the American determination to win is the rest of the world’s satisfaction in seeing them beaten. It would seem that the old ideological frontier between Eastern and Western Europe has, in sport at least, been replaced by a new divide in the centre of the Atlantic Ocean. For some, bread has become more important than circuses but for others, including, it seems, Vladimir Putin, sport is still seen as a way of promoting a healthy way of life among Russia’s populace as well as one way, if not the best way, of gaining international recognition and prestige.

To sum up, the changes taking place in sport as a sequel to the demise of the political adversary that was communism and the now free rein given to the capitalist concept of ‘profit maximisation’ have far-reaching implications for the 21st Century. To those who regret the erosion of national sports and values in the face of US television culture in the wake of the European communist demise, some trends will not be welcome. Perhaps this will encourage concerted and quality-based action to enable all Europeans to experience more fully the benefits and values of all sports, traditional and modern. If that happens, the passing of a symbolic foe in sporting arenas will not be a cause for mourning.

Other Works Consulted for this Chapter

- Childs, D. “Sport and physical recreation in the GDR,” in J. Riordan (ed.), Sport Under Communism, London: Hurst, 1978.

- Cohen, S. Failed Crusade, New York: W. W. Norton, 2001.

- Davletshina “Sport i zhenshchiny,” Teoriya i praktika fizicheskoy kultury, Moscow, 1978 (3).

- De Swan, A. (ed.), Social Policy Beyond Borders: The Social Question in Transatlantic Perspective, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1998.

- Edelman, R. Serious Fun: A History of Spectator Sport in the USSR, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Ehrich, D., Heinrich-Vogel, R. and Winkler, G. Die DDR Breiten-und Spitzensport, Munich: Kopernikus Verlag, 1981.

- Gilbert, D. The Miracle Machine, Coward, Toronto: McCann & Geoghegan, 1980.

- Künst, P. Der Missbrauchte Sport: Die Politische Instrumentalisierung des Sports in der SBZ und DDR, 1945-1957, Köln: Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, 1982.

- Kultura i zhizn’, Moscow, November 1, 1949 (11).

- Landar, A. M. “Fizicheskaya kul’tura, sostavnaya chast’ kul’turnoy revolyutsii na Ukraine,” Teoriya i praktika fizicheskoy kul’tury, Moscow, 1972 (12).

- Peppard, V. and Riordan, J. Playing Politics: Soviet Sport Diplomacy to 1992, Greenwich: Jai Press, 1992.

- Riordan, J. Sport in Soviet Society, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

- Riordan, J. Sport, Politics and Communism, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1991.

- Rodionov, V. V. “Sport i integratsiya,” Teoriya i praktika fizicheskoy kul’tury, Moscow, 1975 (9).

- Schmidt, O. Sport in der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, Bonn: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 1975.

- Schneiderman, N. Soviet Sport: Soviet Road to Olympus, Kingston/Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press, 1979.

- Semashko, N. A. Puti sovetskoy fizikul’tury, Moscow, 1926.

- Semashko, N. A. “Fizicheskaya kul’tura i zdravookhraneniye v SSSR,” Izbrannyye proizvedeniya, Moscow, 1954.

- Zedong, M. Une étude de l’education physique, Paris: Maison des sciences de l’homme, 1962 (originally published in Chinese in 1917).

After the Fall: Central and Eastern Europe since the Collapse of Communism. R. Bradshaw, N. Manning, and S. Thompstone (eds.), St. Petersburg, Russia: Olearius Press, 2003.

[1] For an account of sport in the communist era on which this article is based see the brief bibliography at the end of this chapter.

[2] Riordan, J. Sport in Soviet Society, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977, p. 163.

[3] This section is largely based on Riordan, Sport in Soviet Society, op. cit.

[4] As the GDR leader, Ulbricht, put it in 1950: sport is not an end in itself. It is “integral to our anti-fascist democratic system,” Sport in der DDR, Bonn: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 1981, p. 39.

[5] The 1989 census listed 128 nationalities. This has now been expanded to 150. Vremya Novostey, 30th April 2002, p.6 in The Current Digest of the Post-Soviet Press [hereinafter CDPP] 54 (19), 5th June 2002, pp. 5-6.

[6] The lack of detailed records makes it impossible to give precise figures. The Soviet Union’s total direct human losses at 27 million given here are taken from Krasnaya Zvezda, 31st December 1992, p. 3. The figure of 25 million is given in Overy, R. Russia’s War, London: Allen Lane, 1998, p. 3. The population shortfall arising from WWII is much higher – as much as 45 million according to some estimates.

[7] DOSAAF was set up in 1968, its more military focused predecessor organisation being OSOAVIAKHIM, the society for the promotion of aviation and chemical defence. Donnelly, C. Red Banner: The Soviet Military System in Peace and War, Coulsdon: Jane’s, 1988, p. 175.

[8] The recently launched campaign for improved physical fitness is largely modelled on this. See below, p. 17.

[9] Holzweissig, G. Sport und Politik in der DDR, Verlag Gebrüder Holzapfel, 1988, p. 59.

[10] For a long time in the West, sport was seen as a luxury but in the late 1960s the Council of Europe began promoting a programme of sport for all, recognising that lack of physical exercise in industrial societies was a greater source of ill-health than infections or cancer. See: Sport for All in Europe, London: HMSO, 1990, pp. 1-5. Obesity among young people in the West is currently a matter of great concern. See The Times, 10th September 2002, p. 3.

[11] Quoted in Espy, R. The Politics of the Olympic Games, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979, p. 4.

[12] Bernett, H. Körperkultur und Sport in der DDR, Schorndorf: Verlag Hofmann, 1994, p. 11. For a detailed study of drugs misuse in East German sport see Spitzer, G. Doping in der DDR, Köln: Bundesinstitut für Sportwissenschaft, 1998.

[13] Davies, R. America’s Obsession: Sports and Society Since 1945, Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace, 1994, pp. vii and 29-30. See also Creedon, P. J. Women, Media and Sport, London: Sage Publications, 1994, p. 4.

[14] Holzweissig, op. cit., p. 10.

[15] Kommersant, 26th February 2002 in CDPP, 54 (9), p. 6.

[16] Espy, op cit., p. 6.

[17] Ibid.

[18] In the West Indies for example baseball is increasing in popularity at the expense of cricket.

[19] In Scottish football, for example, Glasgow Rangers and Glasgow Celtic make no secret of their desire to join the English Premier Division.

[20] This is particularly apparent in the field of football, where newly independent nations have gained recognition in competitions such as the World Cup and the current European Cup competition. Elsewhere, the 2001 Wimbledon tennis champion, Goran Ivanisovic, saw his victory as a triumph for Croatia.

[21] This can be a two-edged sword. Bosnian Serbs used the recent victory of the rump Yugoslavia in the world basketball championships as a pretext to go on the rampage against non-Serbs. The Times, 4th October 2002, p. 16.

[22] Peppard, V. and Riordan, J. Playing Politics: Sport and Soviet Diplomacy to 1992, Greenwich: Jai Press, 1992, p. 131.

[23] From the late 1920s discrimination against black sportsmen in the United States was an important campaigning issue for the American Communist Party. See Naison, M. “Lefties and Righties: The Communist Party and Sports During the Great Depression,” in D. Spivey (ed.), Sport in America: New Historical Perspectives, Westport: Greenwood Press, 1985, pp. 129-44. For the resilience of racism in post-1945 American sport see Davies, op. cit., pp. 49-61.

[24] Vremya Novostey, 30th January 2002, p. 1 and Kommersant, 29th January 2002, p. 9 in CDPP, 2002, vol. 54 (5), p. 8.

[25] Trushkov, V. (ed.), Gordost’ Sovetskogo Sporta, “Vyacheslav Fetisov,” Moscow: Plakat, 1987. For the evolution of the sports school system see Riordan, Sport in Soviet Society, op. cit., pp. 178-9.

[26] Kommersant, 30th April 2002 in CDPP, vol. 54 (18), p. 14.

[27] Trud, 19th February 2002, p. 8 and Kommersant, 26th February 2002 in CDPP, 2002, vol. 54 (9), p. 6.

[28] Krasnov, M. in Rossiyskaya gazeta, 27th February 2002, pp. 1-2 in CDPP, vol. 54 (9), pp. 7, 20.

[29] Davies, op. cit., charts well sport’s move into the mainstream of US national life.

[30] Barnes, S. “God Bless America, the winningest nation: How the USA changed the face of sport,” The Times, 13th September 2002, p. 50.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Itogi, 26th February 2002, pp. 11-16 in CDPP, 2002, vol. 54 (9) p. 7.

[33] “Soccer-World-Russia coach Romantsev defends World Cup showing,” Johnson’s Russia List, no. 6313, 18th June 2002, p. 4.

[34] Sovetskaya Rossiya, 11th June 2002, p. 1 in CDPP, 2002, vol. 54 (24), pp. 6-8.

[35] Ibid., pp. 6-8. There is selective amnesia on the part of Russian journalists here. Soccer violence was far from unknown in the Soviet era. See Riordan, Sport in Soviet Society, pp. 240-42, 313-14.

[36] Kommersant, 29th January 2002, p. 9 in CDPP, 2002, vol. 54 (5), p. 8.

[37] Vremya Novostey, 30th January 2002, p. 1 in CDPP, 2002, vol. 54 (5), p. 8.

[38] Vremya Novostey, 30th January 2002, p. 1 in CDPP, 2002, vol. 54 (5), p. 8.

[39] Kommersant, 29th January, 2002, p. 9; Vremya Novostey, 30th January 2002, p. 1; and Trud, 31st January 2002 in CDPP, 2002, vol 54 (5), pp. 8, 23.

Добавить комментарий